19 September 2024

P.R. Jenkins

Spotlight Beethoven: “Fidelio”

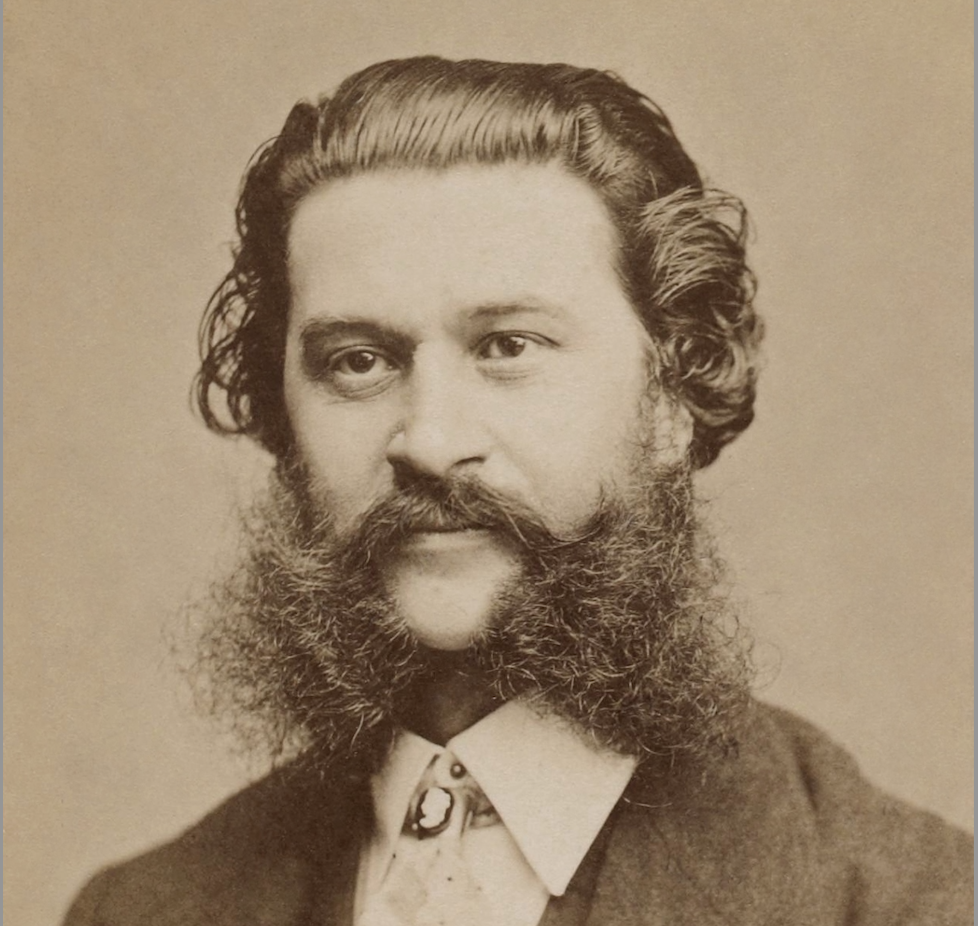

Regarding the importance Beethoven had for Karajan, it is no surprise that his only opera was a cornerstone in the maestro’s repertoire for over 46 years and that there is just one opera that Karajan conducted more often than “Fidelio” (read here which one it is). In his early Ulm years, he started building up his repertoire and added “Fidelio” in February 1932 when he was not yet 24 years old. Two years later, his studies paid off when he was able to conduct a thrilling season to him off on his new job in Aachen. Biographer Ernst Haeusserman quoted a reviewer writing “everybody in the audience was gripped by the strongly emotional tension of this performance” and Richard Osborne added another witness from the press:

“Karajan has at his disposal everything that a conductor, especially an opera conductor, needs: a secure and clear stick technique, great judiciousness, and […] a strongly developed creative will.”

Four years later, on another crucial occasion, it was again a performance of “Fidelio” that brought about the next step in Karajan’s career. He was invited to conduct it at his debut at the Berlin State Opera but argued with the general manager of the State Opera Heinz Tietjen in a number of letters about the work itself. After the “Fidelio” rehearsal, Tietjen came to him and said: “So, you are the great shooting-star. Don’t say anything. Go on conducting the way you have done until now. I heard the rehearsal. We no longer need to discuss these matters.”

The performance on 30 September 1938 was a major success. Richard Osborne mentions the Berlin critic Heinrich Strobel. “Reporting on the audience’s wildly enthusiastic reception of ‘Fidelio’, he concluded his review as follows: ‘[Karajan] has conquered Berlin with a single blow.’”

Karajan conducted “Fidelio” at the Berlin State Opera another 16 times within the next two years. After the war, it took until 1952 before he was engaged for Beethoven’s opera again, this time at his new homebase, the Scala di Milan. The cast was typical for that period: Windgassen and Mödl as heroic couple, Edelmann, George London and Lisa della Casa in other parts. Windgassen, Mödl, Edelmann were also on stage for a concert performance at the Vienna Musikverein on 5 June 1953, this time with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf as Marzelline. Karajan hadn’t been invited to the Vienna State Opera at that time (apart from his pre-war appearances) and tried to attract attention with high-class concert performances, often with the Vienna Symphony.

For the autumn tour of Switzerland, Schwarzkopf was to perform Leonore, a part that isn’t generally associated with her voice and her personality. Richard Osborne asked her many years later if Karajan was satisfied with her. “‘I presume so, ’ she said with a smile. ‘If he hadn’t been, he’d have had no hesitation in replacing me after the first performance.’” Osborne also remarks that her recording of Leonore’s aria “Abscheulicher” with Karajan in 1954 “is a beautifully articulated performance, and a virtuoso one, her voice and the Philharmonia horns led by Dennis Brain symbiotically at one in a thrilling account of the closing bars.”

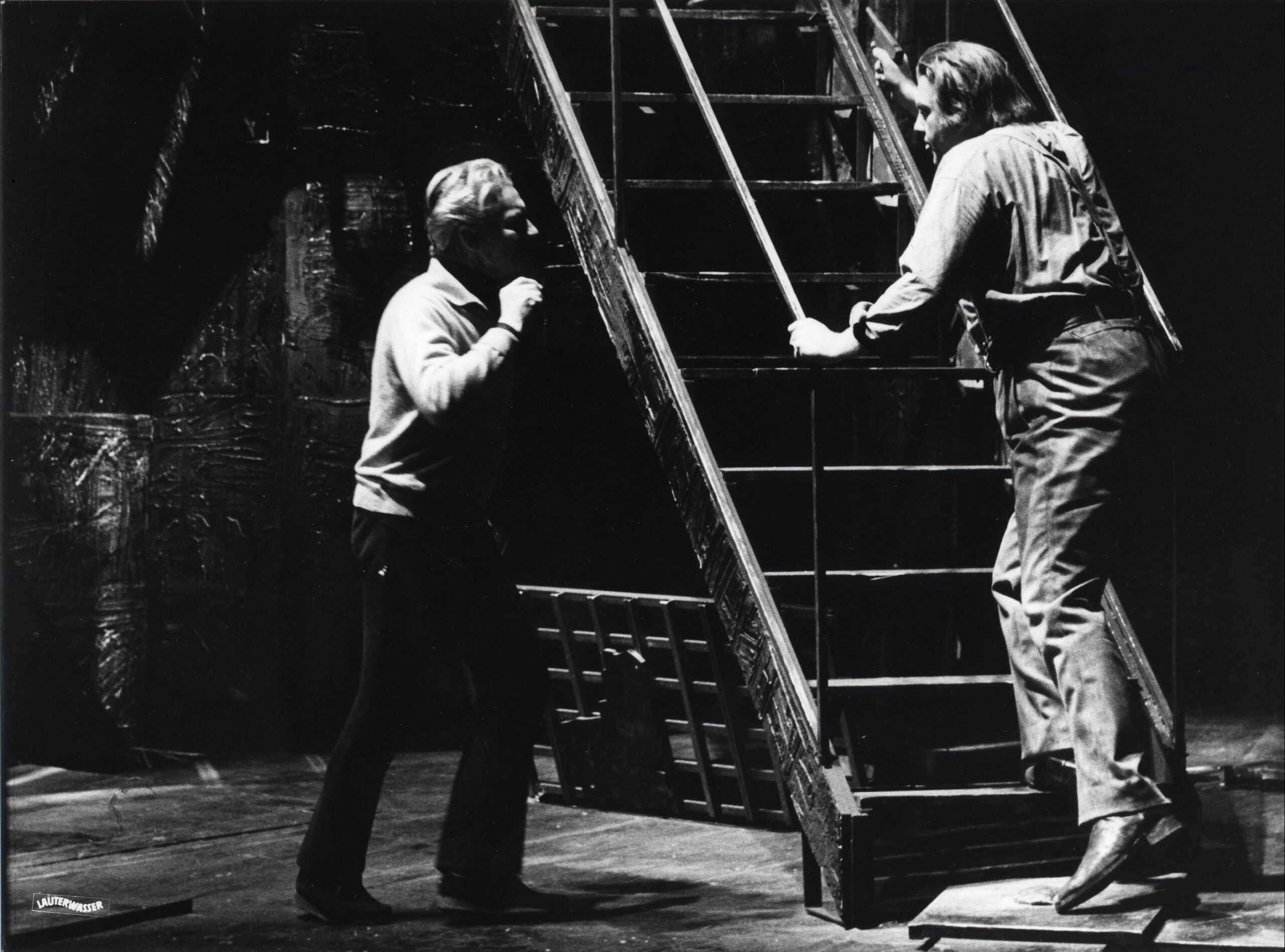

In summer 1957, he conducted and produced “Fidelio” for the first time at the Felsenreitschule Salzburg with Christel Goltz and Giuseppe Zampieri in the main parts and with Edelmann, Schöffler, Kmentt and Jurinac. Between 1958 and 1964, in his era as managing director of the Vienna State Opera, he was in the pit for “Fidelio” on 13 occasions, conducting ensembles featuring as Leonore the incomparable Birgit Nilsson, Mödl, Gré Brouwenstijn, Aase Nordmo-Loevberg, Sena Jurinac, Inge Borkh and – surprisingly successful for herself – Christa Ludwig. Among the tenors were Zampieri, Windgassen and Karajan’s Salzburg Florestan to come, Jon Vickers.

In addition to his many commitments, he also conducted “Fidelio” for the inauguration of the newly rebuilt National Theatre in Munich – his only encounter with the Bavarian State Orchestra. After the second performance, exhausted from the quarrels about the Vienna Opera, he “suffered a sudden physical collapse and was rushed to hospital (Osborne).”

Richard Osborne reports that a few weeks after Karajan’s dismissal from the Vienna State Opera, the last “Fidelio” performances with him in the pit were a “pro Karajan” demonstration. The applause was frenetic and when Florestan asked Rocco: “Who is the governor of this prison?”, some Karajan fans in the gallery yelled “Hilbert!”, the name of Karajan’s adversary in the management. In the second half of the 1960s, Karajan was busy preparing his Easter Festival and the “Ring” operas for it, but in 1971, when the “Ring” was done, he immediately programmed a new “Fidelio” for the Easter Festival before going on to “Tristan” and “Meistersinger”.

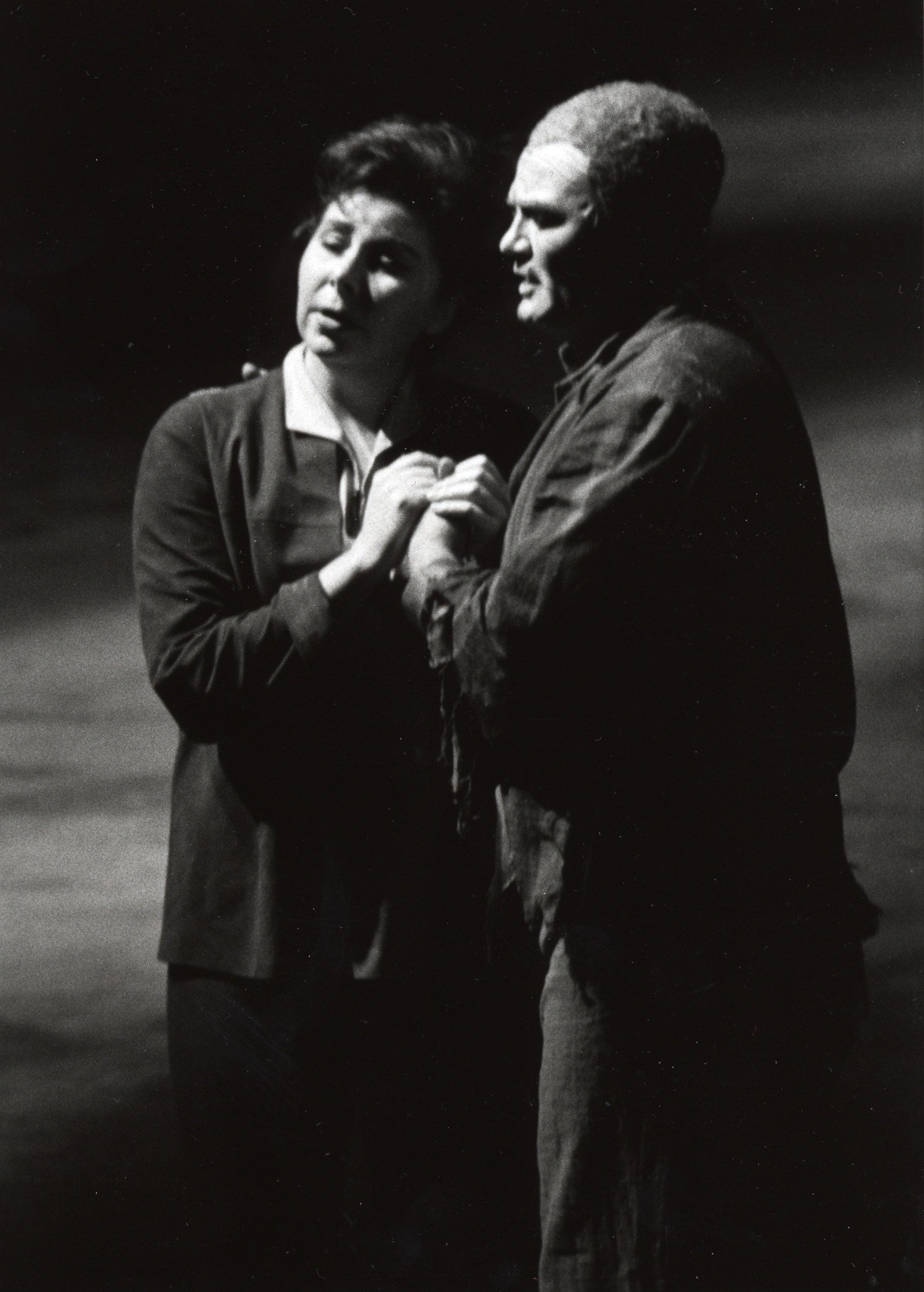

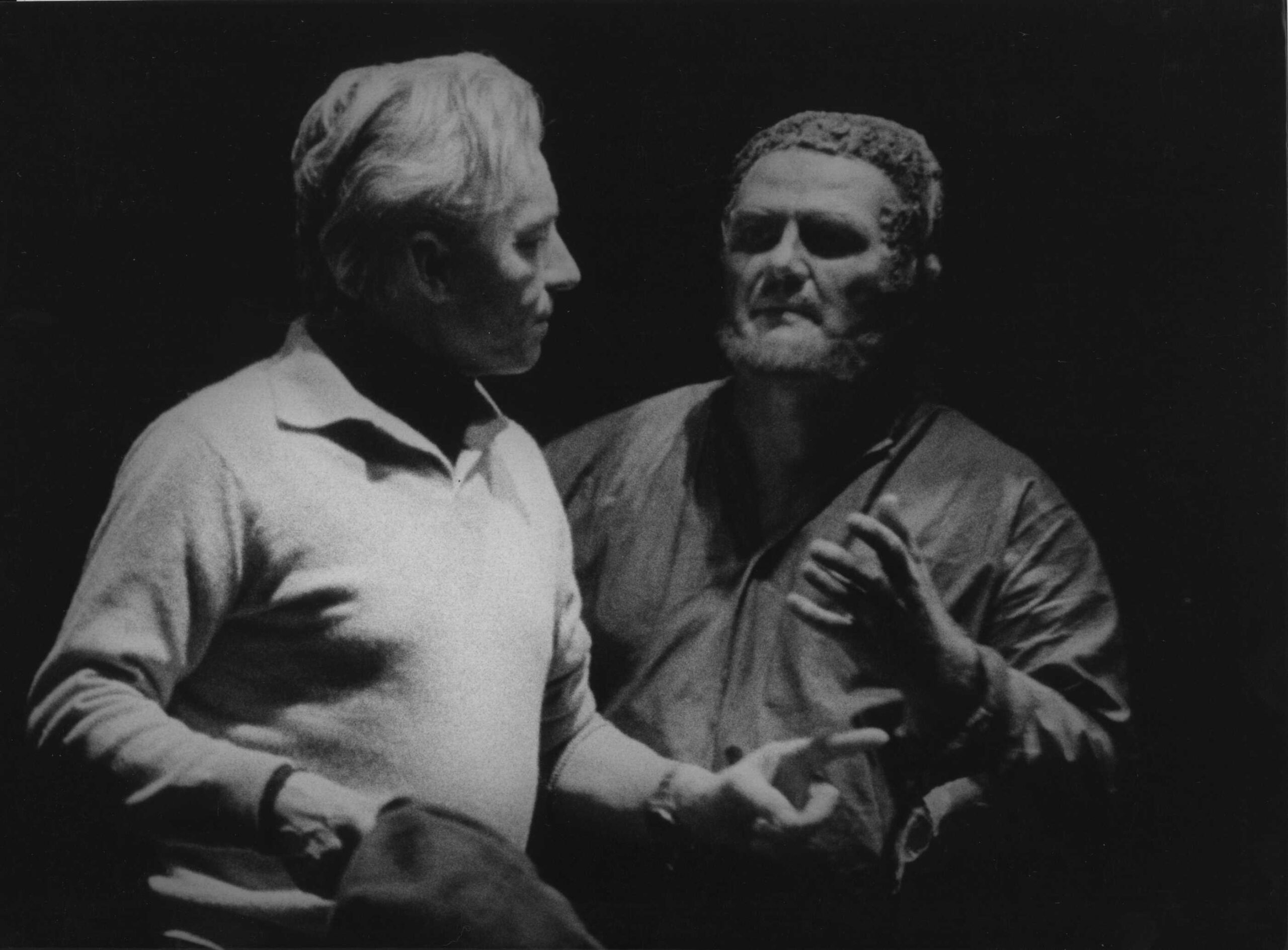

The main parts were played by two of Karajan’s favourites: Jon Vickers as Florestan and his former Brünnhilde Helga Dernesch as Leonore. Among the other singers were Zoltan Kelemen, Karl Ridderbusch, José van Dam and Helen Donath. As in most cases, the production was pre-recorded in the studio. Seven years later, Karajan conducted his last two “Fidelio” performances, again at the Salzburg Easter Festival, with a completely new cast – Hermann Winkler and his freshly discovered Salome Hildegard Behrens as the brave couple and Sigmund Nimsgern, Paul Plishka, José van Dam (this time as Rocco) and Edith Mathis.

The various “Leonore Ouvertures” remained in Karajan’s repertoire up to 1985.

— P.R. JenkinsRichard Osborne: “Karajan. A Life in Music” Chatto & Windus, London. 1998

Ernst Haeusserman: “Herbert von Karajan. Eine Biographie.” Verlag Fritz Molden, Wien-München-Zürich-Innsbruck. 1978