06 September 2024

P.R. Jenkins

Spotlight Schoenberg: Variations for Orchestra op. 31

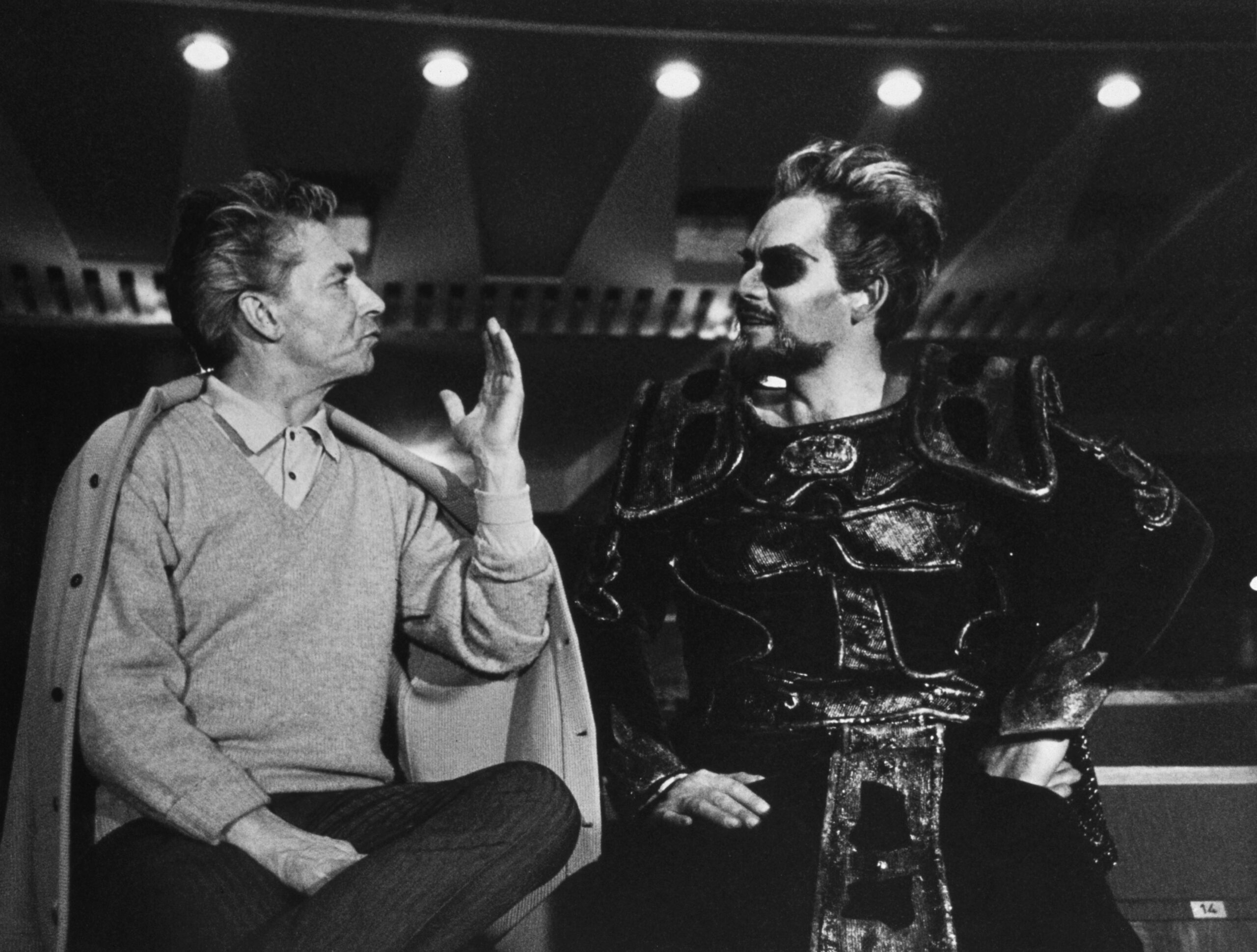

The interpretation of Arnold Schoenberg’s “Variations for Orchestra” op. 31 was one of Karajan’s most ambitious and consistent recording projects ever.

Richard Osborne called it no less than “one of the artistically most successful and technologically most radical of all twentieth- century gramophone recordings.” The result gained the admiration of a large number of critics and listeners, who noted with surprise that he was able to achieve (also financial) success in a repertoire where they had never supposed he would operate.

The Variations are Schoenberg’s first twelve-tone work for orchestra commissioned by Wilhelm Furtwängler and first performed with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1928 (when Karajan was already a student at the Vienna Conservatory). Furtwängler only had three rehearsals for the performance and after that the orchestra was anything but familiar with the groundbreaking work. Karajan had to start from scratch when he put it on a programme for the first time in 1962 (only 11 years after Schoenberg’s death). Richard Osborne notes that Karajan’s friend the musicologist Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt had drawn his attention to the piece. In the following years, “the work became something of an obsession (Osborne)” for Karajan and caused him to initiate rehearsals of single variations in smaller groups of the orchestra sometimes at the very end of other rehearsals, in intervals or in the spare time on tour – a fact that wasn’t always received enthusiastically by the players.

Karajan told Osborne in 1989:

“I began the project with the orchestra several years before we made the recordings. We spent a great deal of time familiarizing ourselves with the music by playing it at subscription concerts and youth concerts. But I knew from the outset that the demands Schoenberg makes in these Variations are abnormal ones which are difficult to realize properly, even in acoustically suitable concert-halls. For the recording, we reseated the orchestra for each variation to create the acoustic that one sees and imagines when one looks at the score. Some people said this was ‘manipulation’ of the music by technology; but it is the very reverse. When Schoenberg asks for the piccolo to play ppp in the top level of its register ‘so schwach wie möglich (as weakly as possible)’ with the bassoon and solo strings at different dynamic levels, and then asks for completely different textures and dynamics in the next variation, I know that this cannot be properly realized by an orchestra in a concert-hall seated in the conventional way. Realizing the Schoenberg Variations was technically the most fascinating thing in the set.”

Karajan’s biographer Peter Uehling quotes Wolfgang Stresemann, manager of the Berlin Philharmonic, in his book about Karajan: “Karajan […] realized that even a large number of rehearsals immediately before a concert wasn’t enough for the orchestra to reach the necessary knowledge of the musical development in the variations with its complicated structure.” That’s why Karajan rehearsed the work even if there was no concert planned. He wanted the familiarity of every musician with the work to achieve an effortlessness that would convince a critical audience. Uehling wrote: “What Stresemann recalls contains Karajan’s entire approach on an interpretation – its genesis and its effect.” Another aspect of Karajan’s Schoenberg is revealing for his musical aesthetics. He was so involved in his “Second Viennese School” project that he wrote an article for the booklet of the vinyl box to explain his goals:

“At our many rehearsals I repeated this again and again: ‘Gentlemen, a dissonance is a tension and a consonance is therefore the necessary and corresponding relaxation. But neither of them, tension or relaxation, can be ugly, because then they no longer constitute music any more.’ […] In our work together we have often rehearsed the intonation for hours on end. The tension too should be a thing of beauty. The musical content must be clean and pure.”

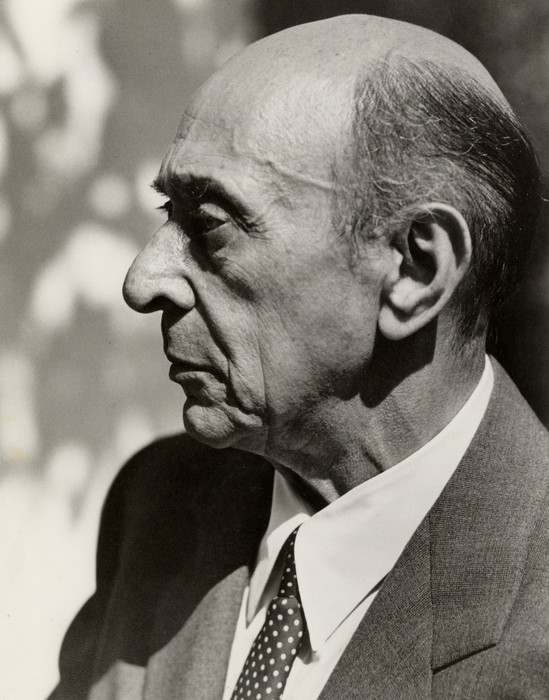

This is a highly interesting, albeit disputable statement. Uehling doubts if composers like Weber, Berlioz, Wagner and Mahler would have agreed but he praises the results of Karajan’s recording and quotes Theodor W. Adorno writing about a concert. Adorno was a philosopher and sociologist but also a pupil of Alban Berg and one of the profound experts on twelve-tone music. As the most influential music theorist in Germany after World War II, Adorno’s scorn for any contemporary composer who didn’t use the twelve-tone technique – like Strauss, Sibelius and Britten – has had an impact on the reception of these composers. Adorno wasn’t particularly fond of Karajan and dismissed him as a “product of the ‘Wirtschaftswunder’” but he admitted his surprise at hearing Karajan conduct the Schoenberg Variations:

“The performance not only surpassed what some minor conductors and aficionados of modern music have achieved but was sensitive to every last detail and so thoughtfully studied and performed that Webern as an interpreter wouldn’t have been ashamed of it.”

Nevertheless, Karajan regarded a satisfying interpretation to be only possible on record, not in concert. He told Richard Osborne in 1989: “There I had the idea of the kind of sound you could never have in the concert-hall, a sound that exists only in the imagination and in the new kind of acoustic reality we were able to create through the recording itself.”

After finishing the recording in 1974, he never conducted the Variations in public again.

Richard Osborne: “Karajan. A Life in Music” Chatto & Windus, London. 1998

“Conversations with Karajan” Edited with an Introduction by Richard Osborne. Oxford University Press. 1989

Peter Uehling: “Karajan. Eine Biographie” Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg. 2006

Theodor W. Adorno: “Einleitung in die Musiksoziologie (Text der Neuausgabe 1968)” Frankfurt a.M. 1975, S. 151