26 January 2023

P.R. Jenkins

Spotlight Mendelssohn: The orchestral works

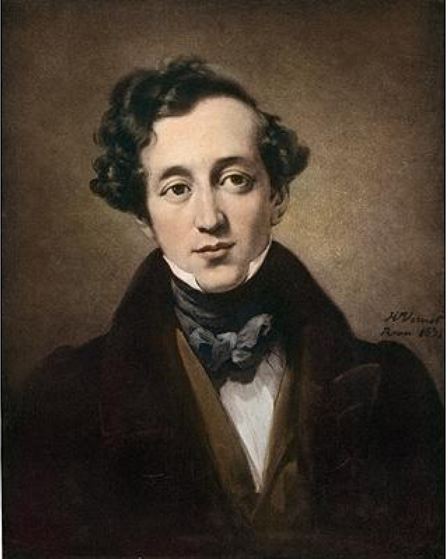

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809 – 1847) was one of the most important and influential composers in the first half of the 19th century, admired by Goethe, Schumann, Wagner and Berlioz, a genius, a prodigy and a European celebrity. Mendelssohn was also one of the first modern conductors to use a baton and insist on regular rehearsals. And he was a leading proponent of a Bach renaissance. At the age of 20 he conducted the “St Matthew Passion” for the first time after Bach’s death.

“The Hebrides” overture

“I would gladly give everything I have written to have composed an overture like Mendelssohn’s Hebrides.”

Johannes Brahms

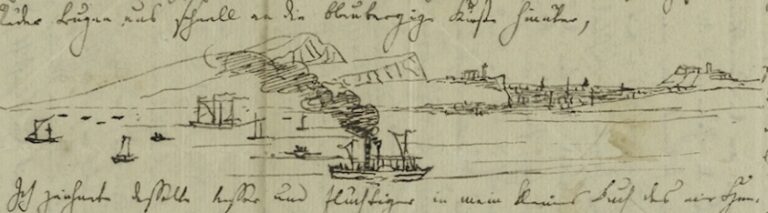

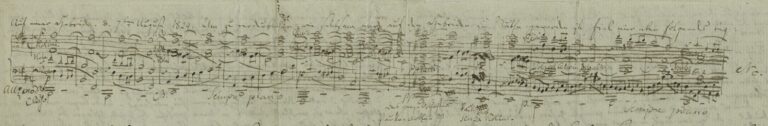

In summer 1829, after his first successful season in London as a composer and pianist, the 20-year-old Mendelssohn visited Scotland with his friend Klingemann. The Isle of Staffa on the Inner Hebrides with its “Fingal’s Cave” inspired Mendelssohn with the idea for a concert overture (he also saved some ideas for his “Scottish” symphony years later) and he started to compose it the following year. After two revisions, the final version of “The Hebrides” was first performed under Mendelssohn’s baton in Berlin in 1833.

“The Hebrides” was the first work by Mendelssohn that Karajan recorded in the studio. Richard Osborne described the 1960 interpretation with the Berlin Philharmonic as “highly atmospheric”. In 1972, Karajan recorded it again with the Berlin Philharmonic.

Symphony No 1

“Some of the best recordings of this period were […] Mendelssohn symphonies.”

Richard Osborne

Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy was one of the most astonishing prodigies in musical history. After he had composed a series of twelve string symphonies, his op 11 was his first “real” symphony in four movements with a duration of about 30 minutes and written for a full symphony orchestra. Mendelssohn was 15 years old. Although there is noticeable influence from the Viennese classics Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, the work is unbelievably confident in form and orchestration. Some parts already resemble the octet and the “Midsummer Night’s Dream” overture, two major works which were to make him one of the most important musical innovators of his time in the next two years – and Beethoven was still composing! The first public performance was in Leipzig in 1827. Referring to another upcoming concert featuring this symphony, Mendelssohn wrote to his friend Henriette Voigt in 1835: “I am actually sorry that my C minor symphony is to be performed at this concert […] If you can prevent the performance, you will do me a favour; if you cannot, it will be easy for you to tell your friends that this symphony […] was written by a 15-year-old boy.”

As we know, Karajan never hesitated to put gifted young musicians in charge for a whole concert, even if they were only teenagers. His 1972 recording of Mendelssohn’s first symphony (I guess the youngest composer he ever conducted) proves him taking this work of a 15-year-old as serious as the better-known symphonies.

Symphony No 2 “Lobgesang”

Mendelssohn symphony No. 2 – but is the “Lobgesang (Hymn of Praise)” op 52 really a symphony? The original version was a cantata commissioned by the City of Leipzig to mark the 400th anniversary of Gutenberg’s invention of the mechanical movable-type printing press, a highly important event both for the publishing Mecca Leipzig and the Protestant Church. After a successful first performance in June 1840, Mendelssohn added instrumental movements and created a work about the length of Beethoven’s ninth symphony. It still remains more a cantata than a symphony and its title “Symphony No. 2” was only chosen by publishers years after Mendelssohn’s death to create a proper list of five symphonies. Apart from No. 1, the numbers of the symphonies are quite arbitrary as Mendelssohn used to re-work different versions of his symphonies over a period of decades.

A major work for soloists, chorus and orchestra from the romantic repertoire – one wonders why Karajan conducted the “Lobgesang” once only for his 1973 studio recording. Just listen to the Allegretto part of the “Sinfonia” where he makes Mendelssohn sound like a melancholic waltz by Tchaikovsky or Grieg …

Symphony No 3 “Scottish”

Mendelssohn’s 3rd symphony was in fact his last completed symphony but it was published as No. 3 because the “Italian” and the “Reformation” were only printed after his death. The popular name “The Scottish” refers to the inspiration Mendelssohn received during his Scottish journey in 1830, especially his visit to Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh. He wrote in a letter: “Today, at twilight, we went to the palace where Queen Mary [Stuart] lived and loved. […] It was all broken and rotten and the bright sky was shining in. I think I’ve found the beginning of my Scottish symphony today.”

Mendelssohn actually never authorized the name “Scottish”. The first performance was in Leipzig in 1842 and the symphony is generally held to be Mendelssohn’s most mature essay in this genre.

The “Scottish” is the Mendelssohn symphony Karajan performed most often in concert, significantly in 1972, 125 years after the day on which Mendelssohn died. Richard Osborne wrote about Karajan’s only studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1971: “The Mendelssohn cycle was similarly fresh-voiced, Karajan’s intuitions working to particularly good effect in a fine recording of the Scottish Symphony, where the infamous peroration, robbed here of all pomposity, sails confidently home, banners streaming in the breeze.”

Symphony No 4 “Italian”

Mendelssohn’s “Italian” symphony is certainly one of his best-loved works. The irresistible verve of the first and last movements and the romantic melancholy of the second are distinctive attributes of Mendelssohn at his best. After his Scottish journey, the young composer travelled to Italy in 1830 and soon began to make sketches for a symphony inspired by Italian music and landscapes (“Saltarello” is the title of the finale). In Rome, he wrote to his sister Fanny: “The Italian symphony is making great progress. It will be the jolliest piece I have ever done, especially the last movement” but he only completed the first version in 1833 when he was back in Berlin. The second movement may be a musical reaction to the death both of his teacher Carl Friedrich Zelter and Goethe (whom he knew personally) the year before. The first performance of the symphony in London in May 1833 was a tremendous success, but Mendelssohn – self-critical as so often – hesitated to publish it. He started revisions but left them unfinished at his death in 1847. The first publication was in 1851, years after the “Scottish”, which is why the “Italian” is still known as his 4th symphony.

Florence, painted by Mendelssohn in 1830

Like most of the Mendelssohn symphonies, Karajan recorded the “Italian” only once, in 1971, and never performed it live. This is quite surprising if one recalls that throughout his career Karajan was considered to be a specialist for the German romantic symphony and was also definitely one of the finest non-Italian conductors of Italian music. Nevertheless, Gramophone described the symphony recordings as “splendid performances, performances in which the greatness of this music is never in doubt and in which its weaknesses, if such they be, are scarcely apparent.”

Symphony No 5 “Reformation”

The symphony No. 5, the one with the highest number, was actually Mendelssohn’s second. Written in 1829/30 on the occasion of the tercentennial of the “Augsburg Confession”, between Mendelssohn’s epochal rediscovery of Bach’s St Matthew Passion and his journeys to Scotland and Italy, it was published as No. 5 in 1868, more than 20 years after Mendelssohn’s death. Mendelssohn – born into a Jewish family in 1809 – was baptised when he was 7 years old. For the symphony he used significant vocal themes of the Protestant church, the “Dresden Amen” and the choral “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott (A mighty fortress is our god)”, but employed neither singers nor chorus. Unlike symphony No. 2, No. 5 is purely instrumental. Mendelssohn’s sister Fanny suggested the name “Reformation Symphony” and that is how it has been known to this day. Because (due to an illness) Mendelssohn couldn’t complete the symphony in time for the anniversary, its first performance was only two years later in Berlin. Like his first symphony, Mendelssohn later in his life regarded the “Reformation Symphony” as an immature work and never performed it again.

Like every symphony of Mendelssohn except the “Scottish” Karajan conducted the “Reformation” only once for his studio recording in 1972 and never in concert. According to Ivan March the reason could have been this: “Karajan’s unerring feel for tempo, his response to the mood and colour of the scores and the spontaneous flow of the music-making are such that he could well have been satisfied that these performances represent the best of him as a Mendelssohn interpreter.”

Violin concerto

“The Germans have four violin concertos. The greatest, most uncompromising is Beethoven’s. The one by Brahms vies with it in seriousness. The richest, the most seductive, was written by Max Bruch. But the most inward, the heart’s jewel, is Mendelssohn’s.”

Joseph Joachim in 1906

Mendelssohn’s violin concerto in E minor is actually his second after the D minor concerto that he wrote at the age of 13 and discarded later in his life. The E minor concerto op 64 (completed in 1844) is a mature masterwork, one of the best-loved both in Mendelssohn’s oeuvre and in the entire literature for the violin. It contains formal elements that are quite innovative for a romantic concerto. The first theme is presented by the violin and not the orchestra, the cadenza is not at the end of the movement but after the development and the second movement is connected with the first by means of a transitional section.

The violin concerto is the Mendelssohn piece Karajan performed most often. His first soloist partner in 1958 was one of his favourite violinists, Christian Ferras. For the five performances between 1959 and 1972 Karajan chose the same model as Mendelssohn himself – the soloist was his concert master. Ferdinand David, leader of the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, performed the concerto for the very first time and Michel Schwalbé, concert master of the Berlin Philharmonic between 1957 and 1985, was also the soloist under Karajan. In 1980, Karajan recorded the Mendelssohn concerto with Anne-Sophie Mutter for the first (and only) time.

We’ve prepared playlists with Karajan conducting Mendelssohn. Listen to them here.

— P.R. Jenkins