16 November 2022

P.R. Jenkins

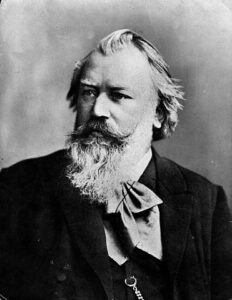

Spotlight Brahms: Your guide to the orchestral works

Brahms’ orchestral works

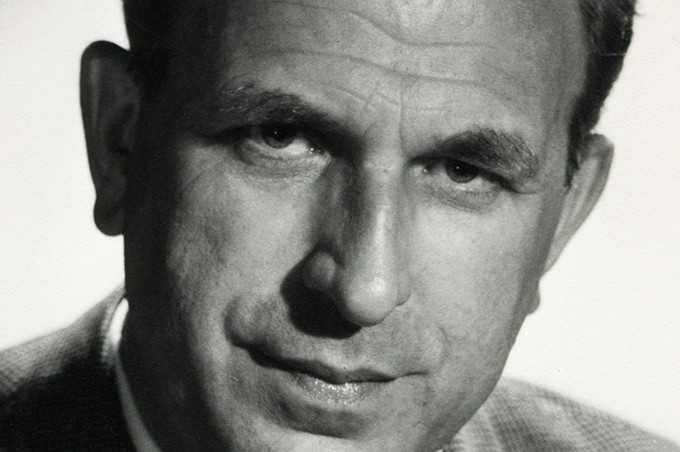

Karajan was a “Brahmsian” with heart and soul. Even if he didn’t perform every of Brahms’ works for orchestra, the symphonies, the concertos and the Requiem have been cornerstones of his repertoire through his entire career.

We prepared playlists of Karajan conducting Brahms’ works on Spotify and Youtube. Enjoy here!

Symphony No. 1

“I shall never compose a symphony! You have no idea what it is like to hear this giant [Beethoven] marching behind you all the time.”

Brahms to a friend around 1870

Brahms took lots of time for his 1st symphony. Early sketches were made in 1862, but he only finished it in 1876 at the age of 43. The first performance was in the same year in Karlsruhe. Apart from some precious chamber works, piano music and songs, Brahms had composed a number of orchestral works by this time, but competing with Beethoven by writing a symphony (the non plus ultra of Viennese classicism) was something that made him hesitate. Aware of the high expectations his audience had of him Brahms chose C minor, the Beethoven key par excellence, and used several Beethovenian elements in the structure. For very good reasons, Brahms’ breakthrough in this genre, to be followed by three other works up to 1885, was estimated in the subsequent decades as “a key work in the history of music (Christian Thielemann)”.

Brahms’ 1st symphony was also a keystone in Karajan’s repertoire. It is the work he recorded most often (on records, in broadcasts or on film) and except for Beethoven’s fifth symphony, there is no work he performed more often in public – 144 times! It is the last piece he ever conducted in Paris and London in autumn 1988 and it is the first (in 1954) and the last (in May 1988) he conducted in Tokyo.

Symphony No. 2

Compared to his 1st symphony, Brahms wrote his 2nd incredibly fast. It was more or less completed during the summer of 1877, which Brahms spent in Pörtschach on Lake Wörthersee. The calm, largely idyllic character of this symphony was perhaps inspired by the Carinthian landscape and has often prompted comparisons with Beethoven’s “Pastorale”. Writing to his friends and to his publisher, Brahms mischievously told them that the symphony “is so melancholy that you will not able to bear it. I have never written anything so sad, and the score must come out in mourning.” Brahms – often seen as an opponent to Wagner – must not have been amused when the first performance in Vienna in 1877 had to be postponed for three weeks, as the Philharmonic was busy studying the “Rheingold”. But the symphony was a success from the very beginning and has been one of Brahms’ most popular works for orchestra up to today. The influential critic Eduard Hanslick wrote: “A great, extensive success crowned the new work. Rarely has the audience’s enthusiasm for a new musical work been expressed so honestly and warmly. (…) Like the sun, the second symphony shines warmly on amateurs and professionals alike, it belongs to everyone who yearns for good music.”

Karajan was very fond of Brahms’ second symphony and performed it almost as often as the first – 139 times between 1935 and 1988. 23 recordings on film, in broadcasts or on records document his constant engagement with the work.

Symphony No. 3

Summer was the best time for Brahms to compose his symphonies. His 3rd was finished in Wiesbaden in 1883. Apart from that, little is known about its genesis. It is his shortest symphony, the only one that ends not in a majestic forte but in a calm and tender mood and the one that contains Brahms’ best-loved symphonic movement, the yearning Allegretto, a “valse triste” recalling Scandinavian composers and even Tchaikovsky (“a pearl, but it is a grey one dipped in a tear of woe” – Clara Schumann). Composing his 3rd, Brahms must have thought of the 3rd symphony, “The Rhenish”, by his mentor and friend Schumann. The beginnings of the two symphonies are strikingly similar both in rhythm and character. Very unusually for Brahms, he returns to the main theme of the beginning at the end of the symphony and gives it a nostalgic glow. A monument for Schumann? Maybe. Schumann’s widow Clara, a close friend of Brahms’, wrote to him in the following year: “All the movements seem to be of one piece, one beat of the heart, each one a jewel! From start to finish one is enveloped in the mysterious charm of the woods and forests. I could not tell you which movement I loved most.” The first performance in December 1883 – the year, Wagner died in February! – turned out to be one of the concert-hall battles between the “Neudeutschen” (supporters of Wagner, Liszt, Bruckner) and Brahms’ supporters. But the success was enormous. Critic Eduard Hanslick wrote: “Many music lovers will prefer the titanic force of the First Symphony; others, the untroubled charm of the Second, but in artistic terms the Third strikes me as being the most nearly perfect.”

Like every other Brahms symphony, the 3rd had a constant position in Karajan’s repertoire between 1936 and 1988.

Symphony No. 4

Brahms’ fourth and last symphony was written in the summers of 1884 and 1885. Why he stopped composing symphonies at the age of 52, having finished his first less than 10 years before, remains a mystery. But his Fourth is a fascinating mixture of serious-mindedness, melancholy and joy in four very dissimilar movements. Having heard the masterly first movement in the piano version, critic Eduard Hanslick exclaimed: “Throughout the movement I had the feeling that I was being given a beating by two incredibly intelligent people.” The second is calm and restrained. The third is Brahms’ only real symphonic scherzo, its scoring includes piccolo and triangle – unusual instruments in Brahms’ oeuvre. And the fourth is a stern passacaglia on a theme like a memento mori, inspired by Beethoven’s C minor variations. Having finished his Fourth in 1885, Brahms sent it to his friend Elisabeth von Herzogenberg and wrote: “The cherries never get ripe enough to eat in this part of the world – so if the thing is not to your taste, don’t hold back. I have no desire to write a bad No. 4.” That year, Brahms was spending his holidays in Mürzzuschlag, Styria.

Brahms’ Fourth was on the programme for a momentous concert in Karajan’s life. The first concert with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1938 was the beginning of a relationship that lasted for over 50 years. With “all the impudence of youth”, the 30-year-old Karajan insisted on rehearsing separately with different sections of the orchestra. He later recalled the argument he had with the leader of the Berlin Philharmonic: “‘We’ve never done that before.’ ‘I think you’ll see I’m right after five minutes.’ ‘Yes, but we know this piece!’ ‘Well, we’ll see, shall we?’ I then went straight to the hardest sections with the violas, and they couldn’t manage them at all.”

In 1989, Karajan told his biographer Richard Osborne:

“I once was engaged to conduct a concert in Mannheim and the pianist who had been engaged was Frederic Lamond. I had on the programme Brahms’ Fourth Symphony and at the rehearsal Lamond said to me, ‘You know, I knew Brahms; I heard him conduct this piece.’ You can imagine the effect this had on me. I was terrified. Later on there was a reception. Lamond was talking to some people and then as he was leaving he came by me and said, ‘But, you know, it wasn’t all as beautiful as you might imagine!’

Some things at that time were no doubt very good; but I suspect if we could hear some of them now we simply would not tolerate them.”

Violin concerto

Brahms’ only violin concerto was his first solo concerto after twenty years. Like many of his mature orchestral works, he composed it during his summer “holidays” in Pörtschach. Because Brahms was a pianist and not a violinist, he asked his old friend Joseph Joachim – one of the most famous violinists of the 19th century – for advice on how best to exploit the instrumental possibilities. Although the solo part is noticeably difficult, Brahms didn’t write a glittering virtuoso showpiece, but rather a kind of symphony with additional violin. Therefore many soloists in the 19th century like Wieniawski refused to perform it. Sarasate found it inacceptable that the main theme in the slow movement is played by the oboe first and not by the solo violin. Today, the concerto is an indispensable piece in every soloist’s repertoire. Joseph Joachim was the soloist of the first performance on New Year’s Day in Leipzig in 1879 and he insisted on playing it in the second half of the concert with Beethoven’s concerto, written in the same key, in the first half. “A lot of D major!” Brahms sighed.

Since his time in Aachen in the 1930s, Karajan performed the concerto regularly with soloists like Wolfgang Schneiderhan, Nathan Milstein, Zino Francescatti and David Oistrach. Studio recordings were produced with Christian Ferras, Gidon Kremer and Anne-Sophie Mutter.

Piano concerto No. 2

Brahms’ 2nd piano concerto was written between 1878 and 1881, about 20 years after his first, in his period of great orchestral masterworks like the symphonies and the violin concerto. The 2nd piano concerto is a work Brahms himself performed quite often, including the first performance in 1881. By 1886 he had played it 40 times in public. As usual, Brahms amused himself by misguiding his friends about his new works. He wrote to Elisabeth von Herzogenberg: “I want to tell you that I have written a very small piano concerto with a very small and pretty scherzo.” The “very small piano concerto” takes about 50 minutes and is still the longest piece in the standard repertoire for solo piano and orchestra. Like all Brahms’ concertos, the 2nd piano concerto is not a virtuoso showpiece. The solo part is strongly connected with the orchestra in an almost symphonic manner. Similarly to the violin concerto, for example, the main theme in the slow movement appears first in the orchestra (played by a solo cello) and only three minutes later in the piano part.

Talking about Karajan and Brahms’ 2nd piano concerto leaves us with one question: What about the 1st piano concerto? Did he never conduct that? No. And it remains a mystery why he didn’t. Richard Osborne reports that Karajan changed the subject when this piece was mentioned, as if there were some kind of curse on it. But he made wonderful studio recordings of the 2nd with Hans Richter-Haaser and Géza Anda and performed it live with Wilhelm Backhaus, Maurizio Pollini and Alexis Weissenberg.

Double concerto

Concertos for more than one solo instrument and orchestra were rare in the late 19th century and Brahms’ Double Concerto is by far the most important of them. In the Baroque and Classical eras, this genre was more popular. Two works that may have been an inspiration for Brahms are Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola and Beethoven’s Triple Concerto for piano trio and orchestra. Brahms’ last work for orchestra was written (as usual) during his summer holidays in Thun, Switzerland in 1887, ten years before his death. It has often been recognized as an act of reconciliation towards his old friend the violinist Joseph Joachim, first interpreter of the violin concerto. In the years before, Joachim had been divorced from his wife Amalie, but both Brahms and Max Bruch blamed Joachim for his baseless jealousy and sided for Amalie – which Joachim resented. Having finished the concerto, Brahms wrote immediately to Joachim: “Brace yourself for a small shock! I couldn’t resist the ideas I had for a concerto for violin and cello, no matter how much I tried to talk myself out of it. […] Above all, I beg you with all my cordiality and friendliness that you don’t hold back. If you just write me a postcard saying ‘No thanks’, that will be enough.” Joachim agreed, and the same year in October, the first performance of the Double Concerto with Joachim and the cellist Robert Hausmann took place in Cologne.

Between 1937 and 1984, Karajan performed the concerto regularly but not very often with violinists Georg Kulenkampff, Zino Francescatti, Christian Ferras and Thomas Brandis and with cellists Tibor de Machula, Pierre Fournier and Ottomar Borwitzky. His only studio recording was the one with Anne-Sophie Mutter and Antonio Meneses.

A German Requiem

Brahms’ “German Requiem” is not only one of the most impressive works for choir and orchestra but also a turning point in Brahms’ oeuvre, for it marked the breakthrough for the 34-year-old composer. Later in his life, talking to Johann Strauss, Brahms’ called it his finest composition – and it is definitely his longest. The “German Requiem” is not a requiem based traditionally on the Latin liturgy, like the ones by Mozart or Verdi. The words are in German, selected by Brahms from different sections of the Bible. Rather unusually for him, Brahms presented different versions of his composition in public. After the first performance of the six-movement form in 1868, Brahms composed an additional soprano solo. This final version was first performed in the following year in Leipzig. As often with Brahms, the reception was mixed. There was great admiration for his “craftsmanship”, but also criticism for a lack of Christian content: the name of Jesus Christ does not occur anywhere in the score. The critic Eduard Hanslick wrote: “Since Bach’s Mass in B minor and Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, there has been nothing comparable in this genre to Brahms’ German Requiem.”

Karajan loved Brahms’ Requiem. He performed it in 50 concerts over more than 50 years and there aren’t many pieces he produced more often for record or on film. His first recording in 1947 was the first-ever complete studio recording, featuring Hans Hotter and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf as soloists. Schwarzkopf recalled: “It was very special. Certainly, we were remembering those whose lives had been lost. … So difficult to bring off. The voice up in the ether, the feelings buried beneath.” Other soloists he worked with on the piece were the sopranos Irmgard Seefried, Lisa della Casa, Rita Streich, Elisabeth Grümmer, Ileana Cotrubas, Leontyne Price, Anna Tomowa-Sintow, Barbara Hendricks and Kathleen Battle and the baritones Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Franz Grundheber and – most often – José van Dam.

Tragic overture and Haydn variations

Brahms’ “Tragic Overture” was written during the summer of 1880 in Bad Ischl, the fashionable summer residence of the Austrian emperor and his family. It may have been inspired by Beethoven’s “Coriolan” and “Egmont” overtures but it does not refer to any specific drama in the literatures of the world. Brahms used the sonata form and sketches for a symphony, so with an approximate length of 14 minutes the overture resembles the first movement of a lost symphony more than the symphonic poems of his contemporaries. In the same summer of 1880, Brahms also wrote the “Academic Festival Overture”, a much lighter work, and he compared the two overtures by saying that “one of them laughs, the other weeps”.

Karajan conducted the “Tragic Overture” several times on records or for films but (apart from the television concert in 1986) only five times in concert, all of them in November 1962.

The “Variations on a Theme by Joseph Haydn” are often described as the first independent set of orchestral variations in the repertoire. Brahms wrote the work in 1873, between his early compositions for orchestra (serenades, 1st piano concerto) and his mature symphonies and solo concertos. Brahms came across the theme – also called the “St. Anthony Chorale” – as part of one of Haydn’s divertimentos. Today, musicologists doubt that it is an original composition by Haydn, assuming rather that it was attached to the divertimento by a publisher.

The “Haydn Variations” are a work that Karajan did not try out in his early years in Ulm or Aachen. His first recording with the Philharmonia Orchestra was in 1955, his first public performance on an American tour with the Philharmonia the same year. Up to 1987, Karajan performed the variations regularly and recorded them three more times.

— P.R. Jenkins

“Conversations with Karajan” Edited with an Instroduction by Richard Osborne. Oxford University Press. 1989