08 September 2023

P.R. Jenkins

Karajan artists: Gidon Kremer – recording instead of rehearsing

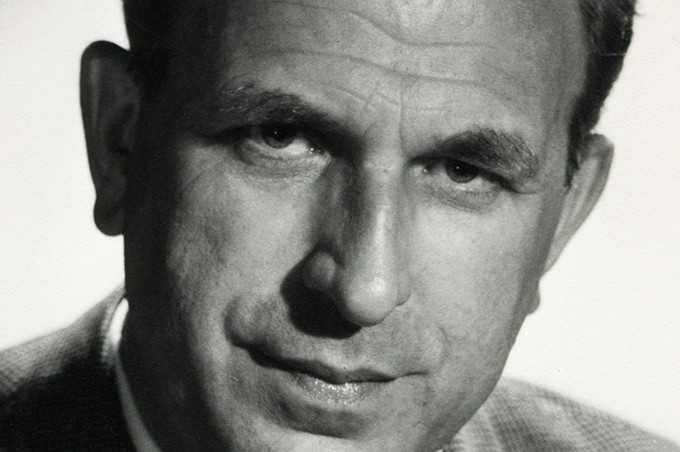

Karajan was not only a conductor with an incomparable sense of what it takes to record music.

In producing high quality recordings his “speed, economy and versatility […] were breathtaking. (Richard Osborne)” Sometimes, for a more spontaneous and relaxed result, he would use the rehearsal tape for the final publication (read the story about Jess Thomas).

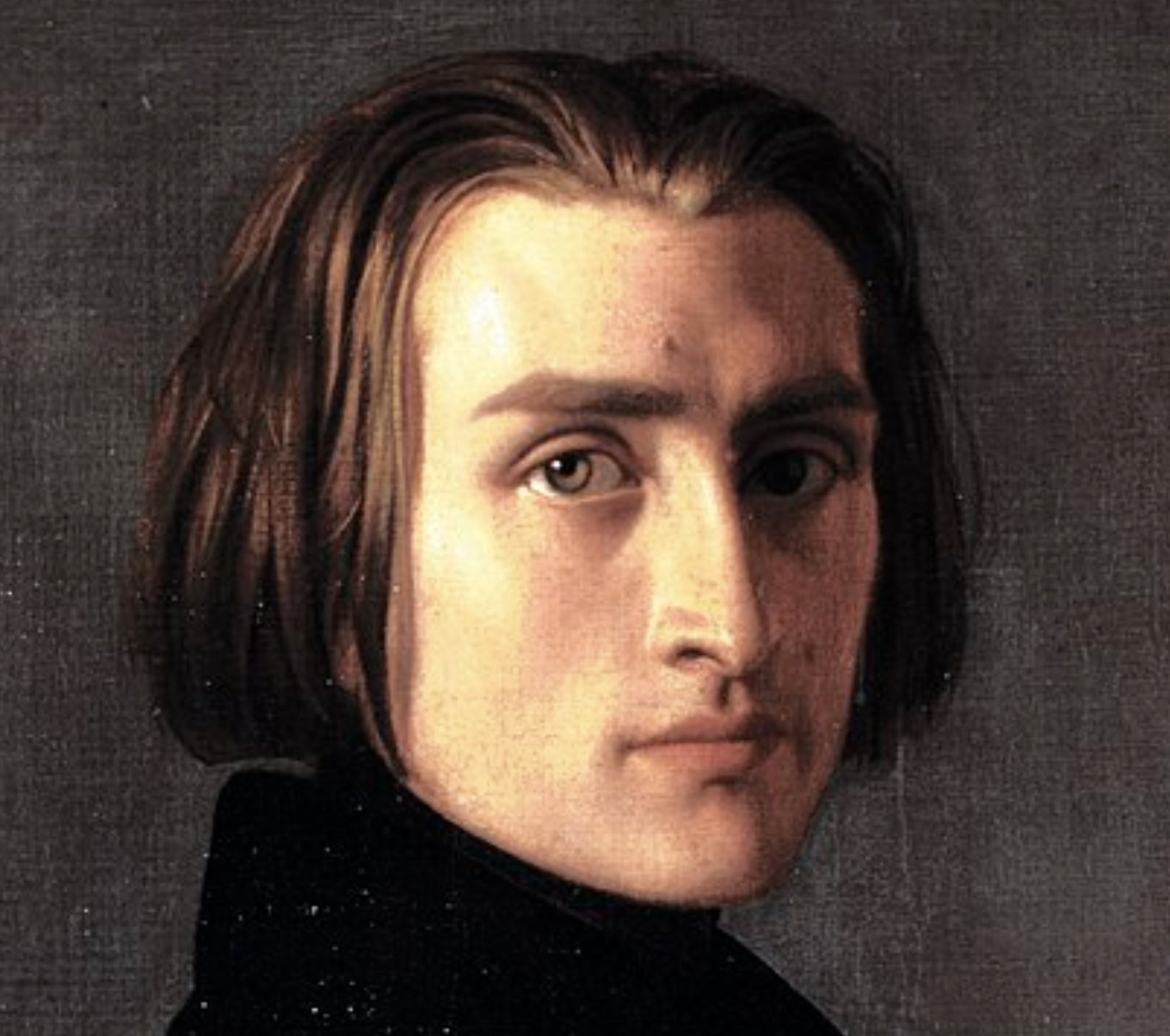

This was something the young Latvian violinist Gidon Kremer (a pupil of David Oistrakh) didn’t know when he came to Berlin on 6 March 1976. It was planned that he, Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic should perform Brahms’ violin concerto in a Sunday afternoon concert at the Berlin Philharmonie the next day. Karajan had just recovered from a life-threatening back operation and was giving his first concert after an interval of three months. He welcomed Kremer to the rehearsal and refused a solo audition: “I already know how you play. Everything will be fine.” Kremer recalled:

“Shortly before, I was told that the rehearsal would be recorded in order to have material for corrections. […] Suddenly it was completely quiet and the recording began. […] It was hard to believe. The ‘rehearsal’ basically turned out to be a recording. Seizing the right moment was part of the maestro’s artistic philosophy. […] The published recording hardly gave the impression of a rehearsal. We did interrupt sometimes, as is usual in correction sessions, but everything worked without any additional effort. The Berlin Philharmonic, performing the well-known Brahms sound voluminously and colourfully, was of course able to generate production processes, monitoring and balance adjustment of the highest quality out of nothing. […] Karajan led the whole enterprise with the utmost authority, demonstrating a natural approach to high art. […] He was in a good mood, listened carefully, tried to adjust one thing or another. Generally, apart from the ‘assault’ on a young artist, he was extremely fair. It was not only his remarks, it was his presence that was intimidating. […] The whole session, including the studio, lasted about two hours plus about an hour and a half the next morning. The cadenza was produced later when the orchestra had already left. The recording was finished.”

Kremer relates how he panicked when he realized that the rehearsal in fact was the recording and how he got through it without collapsing. The concert the next day (which was consequently not recorded) was a completely different matter.

“The Sunday afternoon concert, Karajan’s first public appearance after difficult surgery, was a unique experience for me. The audience welcomed the maestro with standing ovations. It lasted for minutes that seemed like an eternity to me. I didn’t know what to do with my violin during this ovation for the maestro. The concert was relaxed and free and therefore much more exciting in musical terms.”

In an interview shortly after, Karajan called Kremer ‘the best violinist of our time’. This praise was for many years both motivating and intimidating for Kremer.

“Certainly, the maestro’s praise was well-intentioned. It was part of Karajan’s agenda to support young artists he had worked with successfully. I always saw his loyalty as a gift that gave me strength. […] Maybe the concert was the reason for Karajan’s praise. Maybe something really did happen in our performance that made him make that emotional statement. However – the 40 minutes of Brahms that Sunday afternoon I experienced as something precious and unforgettable.”

Four months later, Kremer and Karajan met for the second and last time for Bach’s E major concerto with the Vienna Philharmonic in Salzburg. Gidon Kremer is now 76 years old and still active on stage and in the studio.

— P.R. Jenkins“Gidon Kremer – Zwischen Welten” Piper Verlag GmbH, München, 2003

Richard Osborne: “Karajan. A Life in Music” Chatto & Windus, London. 1998