18 May 2023

P.R. Jenkins

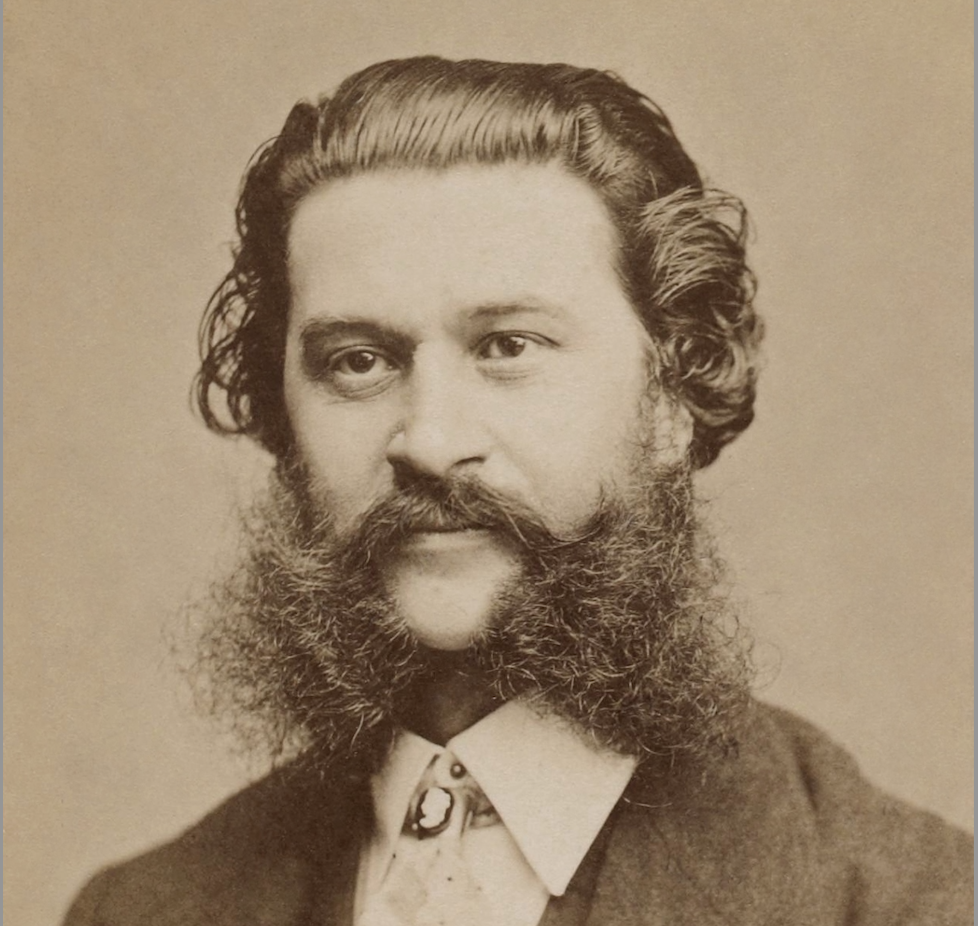

Spotlight Tchaikovsky: “Romeo and Juliet”

“For Karajan … the work was a miracle of dramatic and atmospheric tone-painting.”

(Richard Osborne)

Like many of his early masterworks, Tchaikovsky’s overture “Romeo and Juliet” had a difficult genesis. Tchaikovsky only decided to become a professional composer at the age of 22. He had already worked as an official in St Petersburg when he started his musical studies despite the opposition of his family. He was more or less destitute and dependent on the active help of the distinguished musicians Anton and Nikolai Rubinstein in Moscow. Another supporter was Mili Balakirev, who proposed Shakespeare’s play to Tchaikovsky after having talked to Berlioz about the topic. In 1869, Tchaikovsky completed his overture which failed at the first performance. Balakirev thought that the piece had to be revised profoundly and convinced Tchaikovsky of his changes. But it was only the third version in 1880 that satisfied Tchaikovsky and found its way into the repertoire. In Vienna, the overture was performed for the first time in 1876 by the Wagner (and Elgar) conductor Hans Richter. The influential critic Eduard Hanslick – a friend of Brahms’ – excoriated it and it took ages before it was rehabilitated.

Richard Osborne wrote about Karajan’s first recording in Vienna in 1946: “There was one piece recorded during this period, however, which was far from being an orchestral lollipop. Indeed, its musical qualities came as something of a revelation to the Vienna Philharmonic. It was Tchaikovsky’s Fantasy Overture Romeo and Juliet, a six-sided set recorded in a couple of days right at the end of October 1946. The critic Hanslick had roundly abused the piece on the occasion of its Viennese première in 1876 and little had been done since then to restore its reputation. For Karajan, however, the work was a miracle of dramatic and atmospheric tone-painting.”

Karajan performed it quite rarely in concert (maybe it was because of its duration: 22 minutes, twice as long as a usual overture, a little too long to be put before a solo concerto but too short to be the only work in the first part of a concert) but added three more studio recordings with the Vienna Philharmonic (1960) and the Berlin Philharmonic (1966, 1982) to his discography.

— P.R. JenkinsRichard Osborne “Karajan. A Life in Music” Chatto & Windus, London. 1998