08 December 2023

P.R. Jenkins

Spotlight Bartók: “Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta”

It is often said that Karajan wasn’t all that interested in contemporary music and when he conducted it, his commitment to a specific piece wasn’t unswerving. Bartók’s “Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta” was written eleven years before Karajan conducted it for the first time in public.

Bartók himself was only three years dead. Karajan didn’t conduct it at a festival for modern music nor, in Hungary where the audiences were familiar with Bartók’s music (Bernstein did that in the same year and had a great success in Budapest) – the first occasion was a regular Vienna Philharmonic subscription concert in May 1948. Karajan the crowd pleaser? Not at all.

Although the piece had become quite well known in the years after its first performance “there were enough unreconstituted right-wingers in the Musikverein audience on 8 May for the concert interrupted by catcalls and fisticuffs. Still, it is an ill wind that blows no one any good. The rumpus in the Musikverein delighted the adventurous young manager of the Vienna Konzerthaus, Egon Seefehlner. […] Unlike a lot of people, Seefehlner was quick to see that Karajan was shy rather than arrogant, hard-working rather than bumptious. He knew, as he put it, that they were never going to be ‘chums’; but he fancied he could work with Karajan. It was a trust Karajan would repay handsomely down the years. (Richard Osborne)” (Seefehlner was Karajan’s successor as head of the Vienna State Opera between 1976 and 1986.)

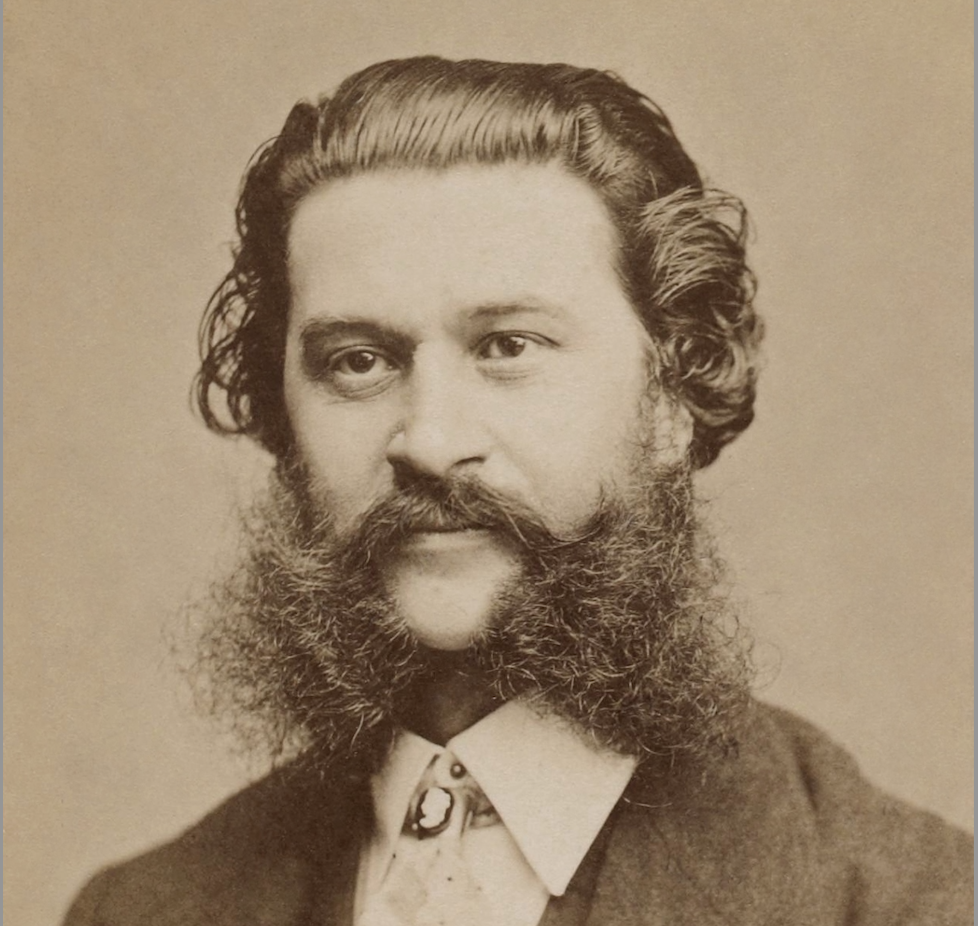

Béla Bartók is one of the 20th century’s most famous composers. Born in Hungary in 1881, he started composing in an impressionist manner combined with elements of national Hungarian music (Liszt, Kodály) and developed a highly original style marked by fiery rhythms and the influence of folk music. With his friend Kodály he also collected over 10,000 folk songs in Hungary, Romania and Slovakia. In 1940 Bartók had to emigrate to the United States where he wrote several works for prominent commissioners (Kussewitzki, Menuhin, Primrose) but at the same time suffered from illness and lack of funds. On 26th September 1945, Bartók died of leukemia in New York.

Karajan’s first recording of the “Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta” in November 1949 was the second ever and one of his earliest with the newly founded Philharmonia Orchestra and its producer Walter Legge.

RICHARD OSBORNE: Legge really stabilized the Philharmonia’s finances and was able to engage you permanently with the orchestra in 1949 as a result of money from the Maharaja of Mysore. Did you ever meet him?

KARAJAN: No, but I was fascinated by this man because he wanted above all things for us to record the Bartók ‘Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celeste’. There was no recording at that time, and it was a very difficult piece for the orchestra to bring off but I was determined to do it. In a way, the very roots of music are touched on in this work.

Jayachamaraja Wadiyar was the last Maharaja of Mysore and reigned over the Kingdom in the South of British India between 1940 and 1950. The Maharaja was a music connoisseur and generously sponsored the recording projects of Legge and Karajan.

Here’s a short clip with Karajan rehearsing the 3rd movement, we assume it is with the Philharmonia because he is speaking English.

Eleven years later, it was the same piece that formed the end of Karajan’s and Legge’s recording collaboration. The 1960 EMI recording with the Berlin Philharmonic was their last project. About Karajan’s last studio recording of the “Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta” for Deutsche Grammophon in 1969, Peter Uehling wrote in his Karajan biography:

“Karajan gets to the spirit of the music and thanks to his tonal imagination he discovers subtle transformations even in the fast movements with their folkloristic fury. Thus, he emphasizes the idiomatic richness of the score in which Hungarian tunes, highly complicated fugues, delicate sound visions, experimental courage and comprehensible expression combine to produce music of unique quality.”

Karajan recalled in 1989:

“I remember when a work like Bartók’s ‘Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celeste’ was thought quite impossible, and we now play it like a Concerto Grosso of Handel. When me made our second Berlin recording we recorded the piece, which lasts 31 minutes, in no more than 40 minutes. The players could have played it without a conductor, we knew it so well at that time. But with all these things I prepared and waited, prepared and waited until I had the orchestra really in hand.”

Karajan performed the “Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta” 28 times in concert up to 1975.

The 3rd movement of the 1969 studio recording was used for a modern cinema classic, Stanley Kubrick’s “Shining”.

— P.R. JenkinsPeter Uehling: “Karajan. Eine Biographie” Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg. 2006

“Conversations with Karajan” Edited with an Instroduction by Richard Osborne. Oxford University Press. 1989

Richard Osborne: “Karajan. A Life in Music” Chatto & Windus, London. 1998