04 April 2024

P.R. Jenkins

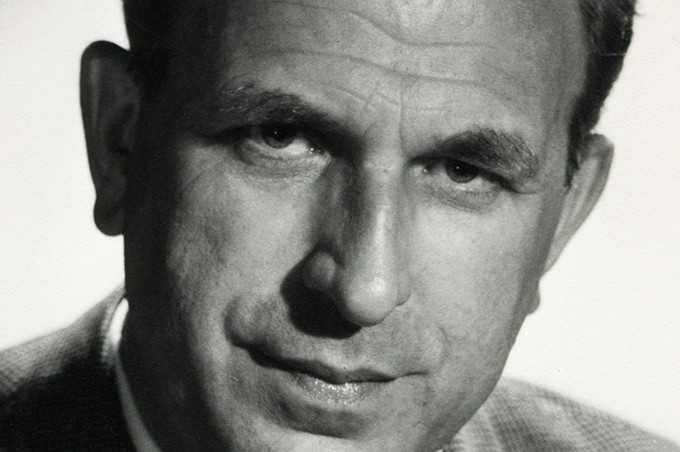

Karajan artists: Yehudi Menuhin – superlative violinist and conductor

“When you conduct an orchestra, it is a very great training in human relationships. You have to look after them, which Karajan did to a remarkable degree.”

“Karajan follows a long line of great conductors, but he is more than a conductor, he is a leader of men.”

Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi Menuhin wasn’t a frequent artistic partner of Karajan’s – in fact, they only joined forces for four concerts and a concert film. But the two men knew each other well and reflected extensively about their respective approaches to music-making. Although Menuhin was eight years younger than Karajan, he achieved star status as a classical musician long before Karajan, having started on his career as a child prodigy at the age of ten. He managed to become the most famous violin virtuoso in the second half of the 20th century and sustained the longest-ever partnership with one record label – his contract with EMI extended over 70 years.

Karajan met him for the first time in Chile in 1949 when he had embarked on a South American tour involving a series of concerts with local orchestras (it was the last time he did anything like this). Menuhin heard him conduct and recalled: “He was already a marvellous conductor, absolutely superb, he got marvellous results.” According to Richard Osborne, Menuhin inspired Karajan to take his first flying lessons. In the following year, they performed for the first time together at the legendary “Bachfest” at the Vienna Musikverein. Menuhin and Wolfgang Schneiderhan played the solo parts in Bach’s concerto for two violins and orchestra, Karajan conducted the Vienna Philharmonic from the harpsichord. Menuhin recalled:

“Karajan was a very good accompanist, quite different from Toscanini who believed there was only one way with the music, which happened to be his way. I got on with Toscanini very well, but in this respect Karajan was not at all like him. My impression was that Karajan was closer to Bruno Walter, who was also a wonderful accompanist.”

The other three live performances between 1953 and 1956 were devoted exclusively to Beethoven’s violin concerto. Their performance with the Philharmonia Orchestra at the Edinburgh Festival on 2 September 1953 was dedicated to the memory of the violinist Jacques Thibaud, who had been killed in an air crash the day before. Another great colleague of Menuhin’s, the young Ginette Neveu, had died the same way in 1949, and Menuhin refused to travel by plane for many years. The two concerts in 1956 were with the Berlin Philharmonic. Many years later, Yehudi Menuhin would write of Karajan’s Berlin Philharmonic:

“There are orchestras, and artists, who have to be restrained, lacking the patience or the inner rhythm to hold a note or a pause. Not so the Berlin Philharmonic: it approaches a note with anticipation and leaves it with regret.”

The last Karajan/Menuhin collaboration was the first Karajan/Clouzot collaboration. In 1965, the French filmmaker started a series of concert films with Karajan. The first session featured Schumann’s fourth symphony and Mozart’s fifth violin concerto. The Mozart was filmed in a Viennese rococo setting illuminated with candles and like the Schumann also included a rehearsal documentary and a “prologue” with Karajan and Menuhin discussing practical problems in music making.

As Karajan mentions, Menuhin at this time had already started on a second career as a conductor. Karajan gave him valuable tips and even encouraged him to conduct a series of concerts in Berlin. Neither of them were entirely happy with the film but it is still a valuable document of their art. In the feature Menuhin says: “When I have a conductor like you, great conductor, who not only accompanies but contributes with his own thoughts and not necessarily the very same ones – because different thoughts, different conceptions can lead to even more interesting and exciting performances – then I’m quite happy and I don’t want anything else.”

Although Karajan’s and Menuhin’s last collaboration took place at quite an early stage (considering that Karajan lived until 1989 and Menuhin until 1999), Menuhin regularly remarked on Karajan’s achievements. There is hardly a more insightful analysis – not of different recordings but of Karajan’s entire style of recording – than this:

— P.R. Jenkins“Karajan worked his interpretations to a fine tilth, aiming at the minimum of sentimentality and the minimum of exaggeration. A recording does not bear hearing more than a few times if you can predict, not the note, but the interpreter’s private twist or change or eccentricity. Karajan wanted a recording that could be heard repeatedly.”

Richard Osborne: “Karajan. A Life in Music” Chatto & Windus, London. 1998

“Conversations with Karajan” Edited with an Instroduction by Richard Osborne. Oxford University Press. 1989