04 July 2024

P.R. Jenkins

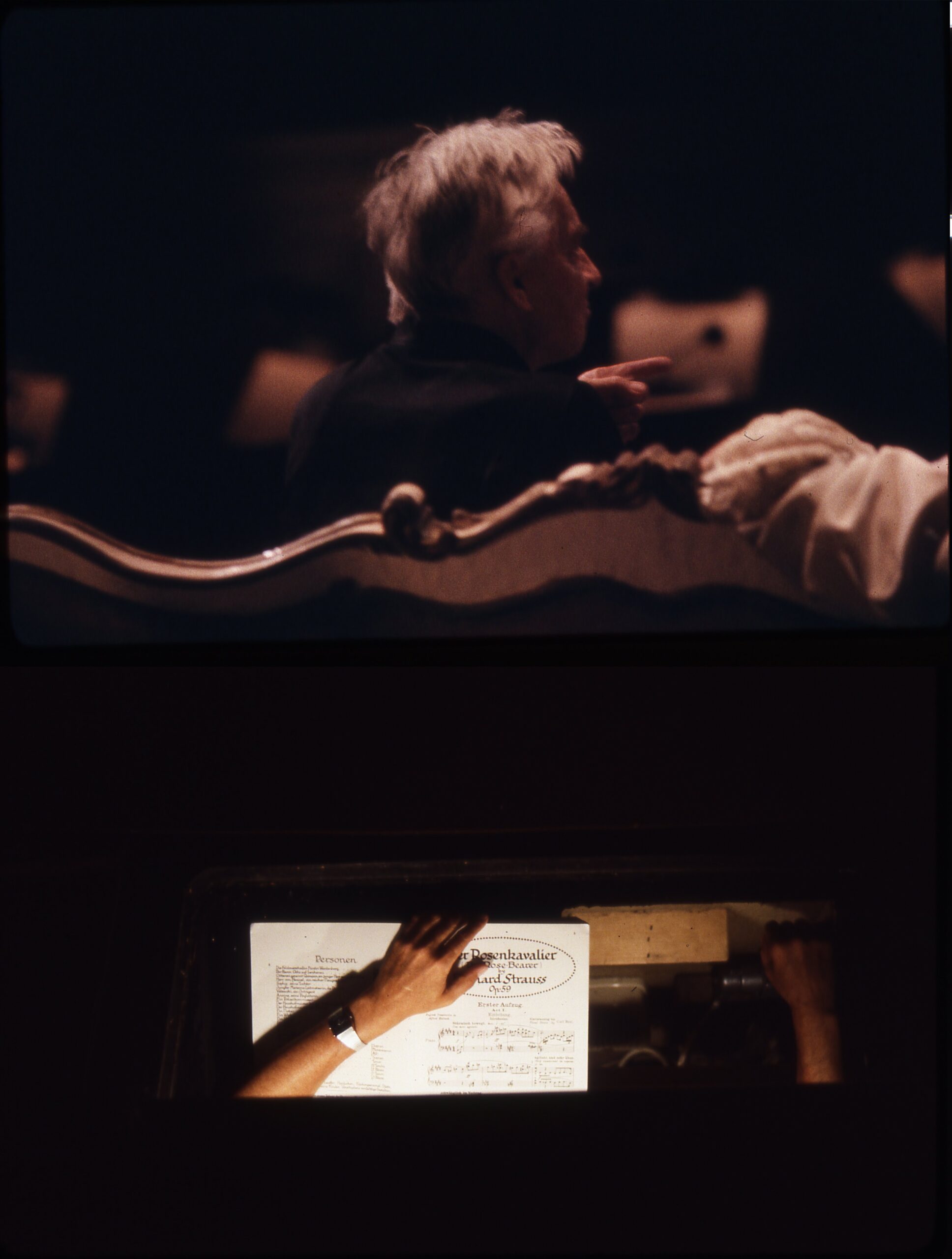

Spotlight Strauss: “Der Rosenkavalier”

“Der Rosenkavalier” was the first original collaboration between Strauss and the Viennese author Hugo von Hofmannsthal (before that, Strauss had turned Hofmannsthal’s drama “Elektra” into an opera in 1909). The premiere in 1911 was so successful that there were special “Rosenkavalier” trains to take theatre-goers from Berlin to Dresden. The director was Max Reinhardt. Together with Strauss, Hofmannsthal and stage designer Roller, Reinhardt was the mastermind of the Salzburg Festival, founded in 1920 in Karajan’s home town, and Karajan was part of his staff in the 1930s. As a great admirer of Strauss (and Reinhardt), it is no surprise that Karajan studied and performed “Der Rosenkavalier” during his first engagement in Ulm in 1932. Karajan told Richard Osborne many years later:

“When I did ‘Der Rosenkavalier’, the man down to sing Ochs came to me and said, ‘I don’t know this part.’ So I said I would teach it to him. Then I discovered he couldn’t read music. So I taught it him at the piano – we had over one hundred sessions. So even now if you wake me at three o’clock in the morning and sing me one bar of ‘Der Rosenkavalier’ I will be able to carry on from where you start!”

As a testimony to Karajan’s success with his first “Der Rosenkavalier”, Osborne quotes the Ulm newspaper: “What we heard from the young musician again yesterday evening is quite unsurpassable given the means at our disposal. An unbelievable vividness of sound grips the listener utterly.”

In his Aachen years, Karajan conducted the opera only twice at an interval of six years. His next attempt was at la Scala di Milano in 1952. He had persuaded Elisabeth Schwarzkopf to sing the Marschallin for the first time. She appeared with Sena Jurinac and Lisa della Casa. Karajan told this anecdote about their stage presence:

“They looked well on stage. This for me has always been important. When the fashion changed after the war, it was difficult for some older singers, just as it was for some of the stars of silent film when the talkies came in. I remember taking ‘Der Rosenkavalier’ to Milan with Schwarzkopf and others. When I arrived at the rehearsal the leader of the orchestra said, ‘Mr von Karajan, I am sorry but we cannot begin; the singers are not here.’ ‘They are on the stage’, I told him. ‘Those are singers?’ he said. ‘I thought they were ballet dancers!’”

One of the rehearsals was rather boring, not even Erich Kunz, who was singing Faninal, came up with any of his amusing witticisms. Karajan interrupted the proceedings and said: “Herr Kunz! Where’s your famous sense of humour? Do you think we hired you for your singing?”

Having recorded three excerpts with Hilde Konetzni, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and the Vienna Philharmonic in 1947, Karajan and Walter Legge set their sights on a complete studio recording of “Der Rosenkavalier”. But it took almost ten years to achieve. In 1956, they assembled the young Christa Ludwig, Teresa Stich-Randall, Otto Edelmann, Eberhard Waechter, Ljuba Welitsch, Nicolai Gedda and – in an iconic performance – “the” Marschallin Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. Karajan conducted the Philharmonia Orchestra (it was Karajan’s and Legge’s last joint opera project). Hilary Finch (Gramophone) wrote about the recording “it really does triumph over them all”. Karajan’s biographer Peter Uehling provides an analysis: “In his 1956 version Karajan interprets the presentation of the silver rose with its famous pseudo-bitonal glitter painting […] ice-cold and calm. The oboe solo evokes an intimacy which reminds us of Mahler’s songs […] the melody appears bucolically simple and the wonderfully wide-ranging singing of Sophie is touchingly fragile in expression. […] Performed like this, it is almost impossible not to think of this phrase as one of the most beautiful in all music.”

Four years later, “Der Rosenkavalier” was the opera to mark a double celebration – the 40th anniversary of the Salzburg Festival and the inauguration of the new Festspielhaus designed by Clemens Holzmeister. Originally, the opening work should have been a Mozart opera – a natural first choice in Salzburg – but the stage was so “CinemaScope” that no director for a Mozart opera could be found. Instead, the choice fell on that most Mozartian opera by the mastermind of the festival, Richard Strauss. Karajan – at the time head of the Vienna State Opera – was the conductor. It may have been an unpleasant surprise for his much-feted Marschallin Elisabeth Schwarzkopf that he chose Lisa della Casa for the opening, although Schwarzkopf was in Salzburg and involved in two other productions. But Schwarzkopf made sure she appeared in the cinema film that Karajan and Paul Czinner produced the same year. Karajan had refused to broadcast the opening night on television because he was worried that a live performance might not achieve the requisite quality.

When the Vienna Philharmonic play Richard Strauss’ “Rosenkavalier”, there is a certain phrase in the 3rd act that they accompany not only with their instruments but also by humming. This is a tradition that started in the days of Strauss himself and Karajan was fully aware of it when he conducted the series in 1960. In the first two performances there were no special incidents but in the third, the musicians decided to tease Karajan and not to hum. Karajan was so perplexed that he nearly missed the next cue and he later said to them: “You mustn’t scare me like this, gentlemen!”

Alan Blyth in Gramophone praised Karajan for his conducting in the 1960 radio live recording: “In the crucial moments at the end of Act 1, while his subtle, transparent treatment of the orchestra is again supreme. You also hear how in the theatre he ‘goes’ with his singers in interpretative inspirations borne of the frisson of singing before an audience.”

Two years later, Karajan took over the production to the Vienna State Opera for a single performance and in 1963 he repeated it at the Salzburg Festival (read the story about Sena Jurinac and watch Karajan rehearsing with her and Anneliese Rothenberger in a rare television clip). In the following Salzburg season, Karajan conducted three performances right after his resignation as manager of the State Opera (it was Richard Strauss’ centenary and Karajan conducted not only “Der Rosenkavalier” during this year but also “Elektra”, “Die Frau ohne Schatten” and a great deal of orchestral music). The performance on 29 August 1964 was remarkable because it was the 150th and last-ever joint performance of Karajan and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf.

Thereafter, Karajan left “Der Rosenkavalier” aside for almost twenty years.

His last production of the opera took place in 1983. Karajan again conducted the Vienna Philharmonic (certainly a premium authority for this music, he never conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in it). His new Marschallin was Anna Tomowa-Sintow. The cast also featured Agnes Baltsa as Octavian, Kurt Moll as Ochs, Janet Perry as Sophie and Gottfried Hornik as Faninal.

Not every critic understood the purpose of Karajan’s new “Rosenkavalier” production and recording but there were also enthusiastic responses. Gramophone wrote: “As happened in his later years, Karajan’s conducting is wondrous in texture, luminous, sumptuous where necessary, but wanting in dramatic point.” And Karajan’s apprentice Seiji Ozawa said to Richard Osborne:

“He had created a deep connection with his musicians and singers, a unity that turned the music-making into something transcendental such as I had never heard before.”

Osborne himself wrote: “Karajan’s ability to enchant singers was never so evident as then.” On 29 August 1984, Karajan conducted his last-ever “Rosenkavalier” at the Salzburg Festival.

In a conversation with Richard Osborne in 1989, Karajan described his interpretation of two main characters in Richard Strauss’ best-loved opera.

— P.R. JenkinsHvK: To some extent Ochs is a ‘type’, but it is true there were many Baron Ochses living in Austria between the wars and living in their castles in a style that was far from elegant – in fact, very uncomfortable, as these were not good times for such people. What annoyed me when I saw Ochs on stage in productions at that time was that he was played as a grotesque, everything greatly exaggerated. But Ochs is not a buffoon. He has been at court, he is an educated man. He may have the smell of the countryside about him but he knows how to behave.

RO: How do you see the Marschallin?

HvK: As a woman who is young in years by our own standards but who is thought old by those of her own time. The end of Act I is a recognition scene; a recognition by the Marschallin of the kind we all experience when we realize that something we cherished is gone for ever. It is not tragic. Tragedy is doing something in spite of the conditions. We come to tragedy through personal misjudgement. But the Marschallin does not misjudge, nor does she sentimentalize the situation. She knows exactly what she is doing.

“Conversations with Karajan” Edited with an Introduction by Richard Osborne. Oxford University Press. 1989

“Immer bekommt der blöde Tenor die Dame” Opernanekdoten. Friederike C. Raderer und Rolf Wehmeier. Reclam. Stuttgart. 2010

“Musizieren geht übers Probieren”. Paul Neff Verlag. Wien 1967.

Peter Uehling: “Karajan. Eine Biographie” Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg. 2006

Richard Osborne: “Karajan. A Life in Music” Chatto & Windus, London. 1998

Alan Blyth on gramophone.co.uk