18 January 2024

P.R. Jenkins

Spotlight Verdi: “Aida”

“The Aida recording will come to be regarded as a landmark on the art of capturing grand opera on disc.”

Andrew Porter in Gramophone

When Karajan conducted “Aida” for the first time in Vienna in 1951, it was not at the State Opera. As with “Carmen” three years later, he caused a stir with a concert performance at the Musikverein. The singers – among others Dragica Martinis, Lorenz Fehenberger and Nell Rankin – sang in Italian which was by no means self-evident back then. Karajan had conducted the work once before in Aachen 1936, of course in German. The Vienna concerts caused spectators and critics to ask why Karajan didn’t conduct more at the State Opera – a discussion he may have intended. And indeed, a few years later Karajan was managing director.

“Aida” was on the programme at the end of his first season in 1958 and he conducted it 16 times before his resignation in 1964. Karajan’s preference for the original language in opera and therefore for Italian singers in Italian operas caused a lot of controversy, not only at the State Opera but throughout Vienna. Christopher Raeburn wrote in Opera that hearing “Aida” in Italian after so many years in German “had the effect of a hazy lantern slide being jogged into focus.” And not only the Italian singers studied and performed the original. The 1958 performances featured a young American singer with whom Karajan worked for the first time and who became one of his most important artistic partners for a period of almost 20 years: Leontyne Price. Other acclaimed singers in those years were Birgit Nilsson, Renata Tebaldi, Gloria Davy, Leonie Rysanek and Martina Arroyo as Aida, Carlo Guichandut, Giuseppe di Stefano, Carlo Bergonzi and Jon Vickers as Radames, Giulietta Simionato, Biserka Cvejic and Christa Ludwig as Amneris, George London, Tito Gobbi and Aldo Protti as Amonasro.

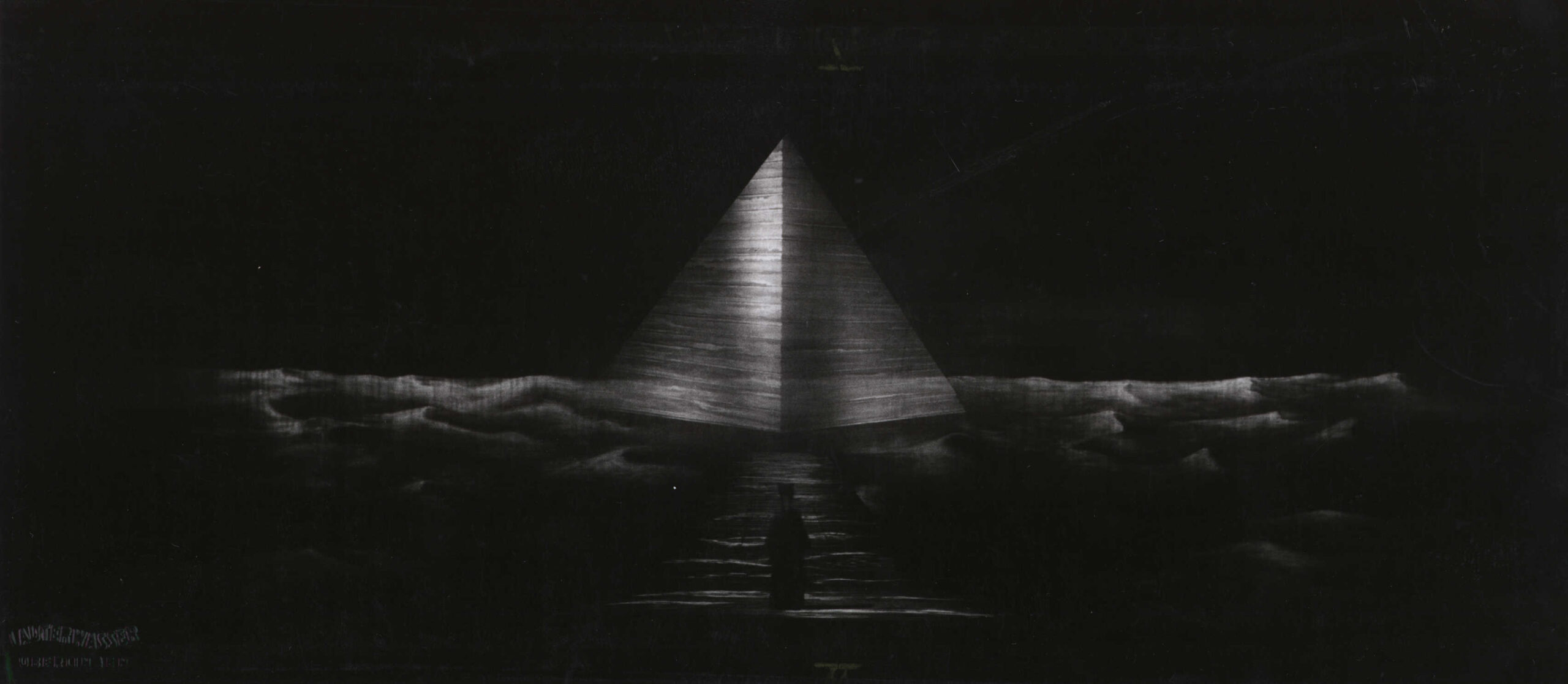

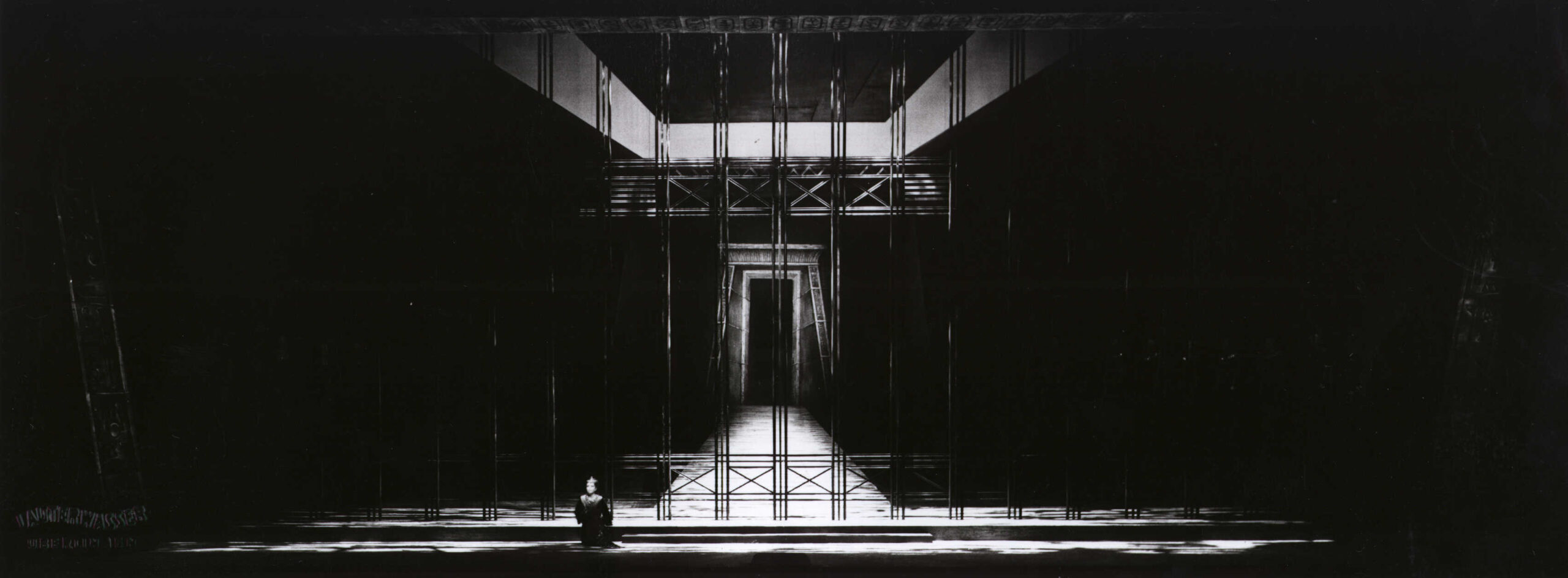

Karajan’s first stereo recording of “Aida” was produced by Decca in 1959 with Tebaldi, Bergonzi, Simionato and Cornell MacNeil in the main parts and the Vienna Philharmonic. Richard Osborne reports: “Karajan knew all about the opera’s problems in the theatre and he was fascinated to re-imagine it in the context of the gramophone. It proved to be a performance of great dignity and power, but one illuminated above all by Karajan’s feel for the audacious delicacy of the orchestral writing […] He would be superbly served by the Vienna Philharmonic […] and by Culshaw’s production which used multi-studio techniques (Karajan was occasionally obliged to conduct with headphones on) to catch the opera’s strange and original mix of remoteness, mystery, and ceremonial splendour in a way that could never be achieved in the theatre.”

“Karajan and Decca producer John Culshaw managed to create a new world of recorded sound, one which came to determine the future direction of opera on disc.”

Warwick Thompson in the CD booklet

During Karajan’s engagement as manager of the State Opera, he conducted “Aida” with several glorious casts. A special performance was the one on 20 March 1962. Karajan had had a conflict with the Austrian government and had offered to resign. The “Aida” performance was his first after having solved the problems – at least for two more years. He was given “a hero’s welcome when he returned to the conductor’s desk (Osborne).” After his withdrawal in 1964, Karajan conducted “Aida” 15 years later at the Salzburg Festival.

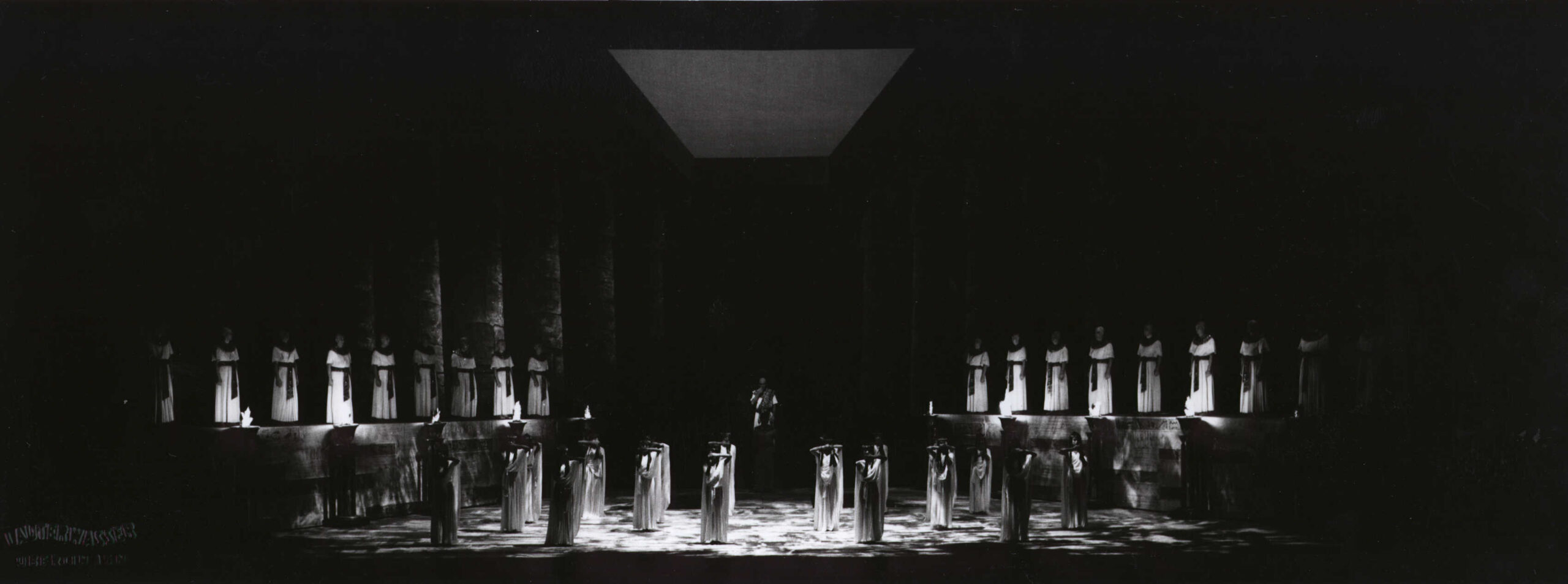

The new production with Mirella Freni, José Carreras, Marilyn Horne, Nicolai Ghiaurov, Piero Cappuccilli, Ruggero Raimondi and the young Thomas Moser was a great success, not only in musical terms. Karajan joked to Richard Osborne about the difficulties of “Aida”: “The shortcomings of this opera are the processions, when people come in with two left feet.” Obviously, he solved the problems of staging (maybe with a little help from choreographer John Neumeier).

As usual, he had produced the recording before and used at the Salzburg rehearsals. That turned out to be a problem for Marilyn Horne as Amneris, who was not involved in the recording (there it was Agnes Baltsa). When Horne also got a cold, it was evident that it wasn’t her production. An anecdote reveals Karajan the never-resting musician. When the 70-year-old maestro conducted an “Aida” performance, he used the interval to sneak off to the Kleines Festspielhaus nearby and listen to Itzhak Perlman playing Bach.

Karajan recorded the overture and some interludes from “Aida” for several compilations between 1954 and 1975.

— P.R. JenkinsRichard Osborne: “Karajan. A Life in Music” Chatto & Windus, London. 1998